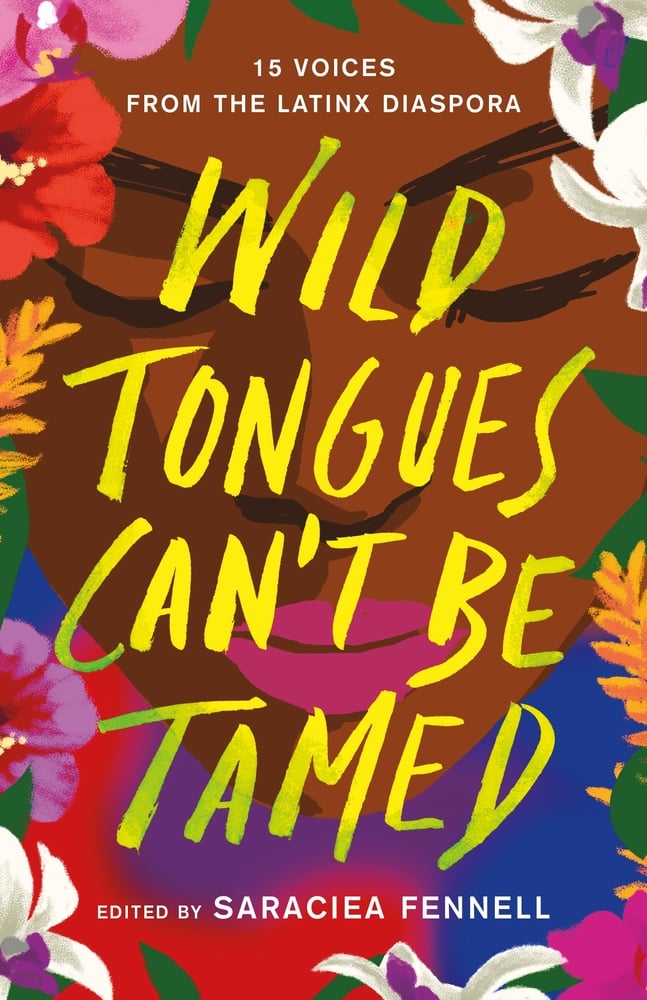

We've been waiting for months in anticipation for Wild Tongues Can't Be Tamed: 15 Voices From the Latinx Diaspora to come out. Edited by The Bronx Is Reading [1] founder and book publicist Saraciea J. Fennell, this beautiful anthology features a collection of authentic and thought-provoking stories written by bestselling and award-winning Latinx contributors that include Elizabeth Acevedo, Cristina Arreola, Ingrid Rojas Contreras, Naima Coster, Natasha Diaz, Kahlil Haywood, Zakiya Jamal, Janel Martinez, Jasminne Mendez, Meg Medina, March Oshiro, Julian Randall, Lilliam Rivera, Ibi Zoboi, and a story by Saraciea J. Fennel herself.

In a time when far too many Latinx authors, among other writers of color, are too often overlooked, Fennel's poetic anthology collection not only tells authentic stories but does away with the monolithic definition of Latiniad we're often accustomed to seeing. It instead speaks to the wide-range of diversity that very much exist within Latinx culture while amplifying the voices and the stories that often aren't given the attention they deserve.

Wild Tongues Can't Be Tamed comes out on Nov. 2 but fortunately, you can get a head start on reading. This exclusive excerpt features writer and contributor Cristina Arreola's chapter "The Land, the Ghosts, and Me" – just in time for Dīa de los Muertos.

El Paso is dry and dusty most of the year, with mountains that sprout from the earth like spiny tortoises, with few trees or bushes as adornment, only cacti brushing along their brown shells. It's a strange and uncanny beauty—a place that could only exist in the realm between the living and the dead and between two countries. When I think of El Paso, I think of the land, and I think of the ghosts.

My father and I always knew there was something in the land of West Texas that existed before us, beside us, and after us. There were shadows and memories that stamped places with their energy and left echoes in the universe.

My mother never saw or felt them, but she never doubted them either. She told me I had a "strawberry" mark on the top of my spine, a physical representation of a spiritual gift: I could see the things that others couldn't. It meant that I could sense the ghosts that brushed at our ankles as we stood in the kitchen or came to whisper at my neck as I played in the den. I could feel the ghosts that sent me running in the night to the comfort of my parents' room, where I stood at the foot of the bed, scared to wake them but too scared to be alone.

"Just ask them to leave," my father told me on the nights when I couldn't sleep. "And they'll go." But it wasn't that simple. "They don't speak like you and me, so you have to think it more than say it," my father said. What kept the ghosts from hearing my thoughts? What if they could hear them all? What if they could use my worst fears against me? After being awoken by spirits in the dead of night, I would run from my bedroom, through the den, and into the pantry. I would rummage through drawers until I found a cloudy plastic bottle filled with Holy Water—a relic from the days when we attended church more regularly. I would douse my fingers in the liquid and sign the cross on my body before running back to my room, where I would sleep with the covers above my head and silently pray under my breath for dawn to break.

We didn't celebrate the Mexican traditions that might have put me at ease. For example, Día de los Muertos—the Day of the Dead—is an exuberant dance with the ancestors, a chance to welcome those who have passed on from this thread of the universe for a little while. In the absence of such joy, I only knew fear. And I was influenced by the ghosts I saw on TV—gruesome, scary, and meant to harm.

What a strange thing it was: To be so close to a culture, of that culture, but to be so removed from the parts of it I needed to feel whole and safe. When it came time for college, I was ready to leave. I wanted the peace of sleep without spirits, and I was convinced I would find it somewhere far away from El Paso. I was bound for the suburbs of Chicago, a place as different from home as any I could have chosen and one that failed to deliver the escape I had desired. In this flat, barren land of perpetual winter, I felt completely estranged from who I had been at home. I was unhappy with my chosen major but couldn't be convinced of a new one. I was shy, and I missed the silly, easy intimacies of high school. I abandoned the things I loved the most— singing, writing—because I was simply too afraid to seek them out in a new form. It stripped me to the bone and laid bare the most essential parts of me.

The spirits were gone too, burrowed somewhere dark and warm where I couldn't find them. The people I met didn't even believe in ghosts—real to me as the snow that poured from the sky every October. Not everyone would acknowledge blurriness at the edge of the horizon or notice the shadows in the periphery, I knew, but I hoped some would. It began to feel as though the world I had been so eager to leave behind was also the only world that would ever make sense to me.

So began my two-step dance of walking back my identity and moving into it, a careful and precise act that lasted for four years. I cannot explain why I did it, except that I wanted to please everyone at all times. When people asked where I was from, I said West Texas instead of El Paso because I was ashamed when people hadn't heard of my hometown. When people learned I was Mexican American, I told them I could speak Spanish because I was embarrassed by my laziness in never having learned. Steam filled my gut as I listened to classmates masterfully conjugate their Spanish verbs, knowing I could barely hold a conversation with people in my own family. I felt exposed by my friends who spoke of their Mexican vacations with delight and authority when I had barely ventured across the border that I could see from my parents' backyard. I blanketed myself in half-truths to hide what I thought was deep humiliation but was really a deep unknowing.

In El Paso, I was Mexican American. Everyone was. But here, making sense of myself wasn't so easy. Away from home, I began to feel that I hadn't been steeped in the culture long enough to make me strong with its flavor, but just enough that you couldn't hide the scent.

How could I claim to be Mexican American when I couldn't speak proper Spanish? When I celebrated so few of their holidays and traditions? The only things I knew were the ghosts and the food. I didn't miss the ghosts, but I did miss the food—my mother's crispy chicken flautas, doused in freshly made salsa and served with a side of chile con queso. Two years into college, I discovered a pizza place near my apartment that served tacos al pastor if you knew to ask for them, and I went multiple times a week, a small and simple pleasure that grounded me to who I had been before. Chicago is home to more than twice the number of Mexican Americans than El Paso, something I would have realized sooner if I spent any time exploring, searching for, or learning of experiences beyond my own. I was too wrapped up in hiding myself to realize that people who could've helped me find my home surrounded me.

I did join a student group for other Latinx students on campus—there weren't many of us—but I was too self conscious to talk about my own complicated feelings about belonging in such a community. We were all so different from one another, and I tried to exist as quietly as possible, awed and ashamed by the scope of my ignorance. I was introduced to Puerto Ricans, Peruvians, Cubans. My entire sense of identity was wrapped around the idea of one specific place—El Paso. I was fascinated by students from New York and Chicago and Miami, who seemed so assured about their place in the world. I never spoke about the ghosts, but maybe they would have understood.

That taste of community led me to the literature class that introduced me to the songs of my ancestors in a way the language hadn't. Even though I grew up on the border, I had only once been assigned a book by a Latinx author. For the first time, at the age of nineteen, I was taught the rich canon of books by and about Latinx people, and in these books, I was shocked to discover the ghosts roamed as free in these pages as they did in my reality.

In Juan Rulfo's Pedro Páramo, a young man travels to a ghost town in search of his father. An older woman offers him shelter, but the room isn't quite ready for him. "A person needs some warning, and I didn't get word from your mother until just now," she tells him. "My mother?" he says. "My mother is dead." "So that was why her voice sounded so weak like it had to travel a long distance to get here. Now I understand."

I was uneasy about the ghosts of this book—both com forted that others saw the world as I did and bereft that this fearsome world existed as I suspected. I left Chicago as confused as I'd found it, but with the knowledge that the world was so much bigger than me and that I was rooted to it in ways I didn't quite understand ...