Tips From a Doctor For Dealing With Tantrums in Toddlers

Tantrums 101: These Doctor-Approved Tips Will Help You Through the Terrible Twos

Angry shrieks, heaving sobs, flailing limbs: any parent who has been through the terrible twos knows just how disruptive temper tantrums can be. Watching your child devolve into a puddle of tears can leave you feeling helpless.

As both a mom of a toddler and a pediatrician, Dr. Julia Pederson knows a thing or two about tantrums. In her practice at the Pediatric Group of Monterey with Stanford Children's Health, she often helps parents navigate this tricky — but nearly universal — challenge. Dr. Pederson says tantrums typically start in the toddler years, and most children experience them between 15 months and 3 years of age.

The reason tantrums tend to peak around the terrible twos? That's when toddlers are learning to interact with the world around them and deal with some big feelings for the first time. "Oftentimes, toddlers don't always have the words to express what they're feeling," Dr. Pederson says. Instead of simply telling you they're upset because they can't eat a candy bar for lunch, they might react by throwing themselves on the floor of the kitchen or screaming at the top of their lungs.

Though tantrums can be triggered by almost anything, Dr. Pederson says one of the biggest causes is a change in routine, like starting day care or moving to a new home. "Transitions can put toddlers in newer, different situations that cause a little bit of stress and can lead to those bigger feelings and emotions," she explains. Anytime your child is hungry, tired, or cranky, you can also expect an uptick in tantrums.

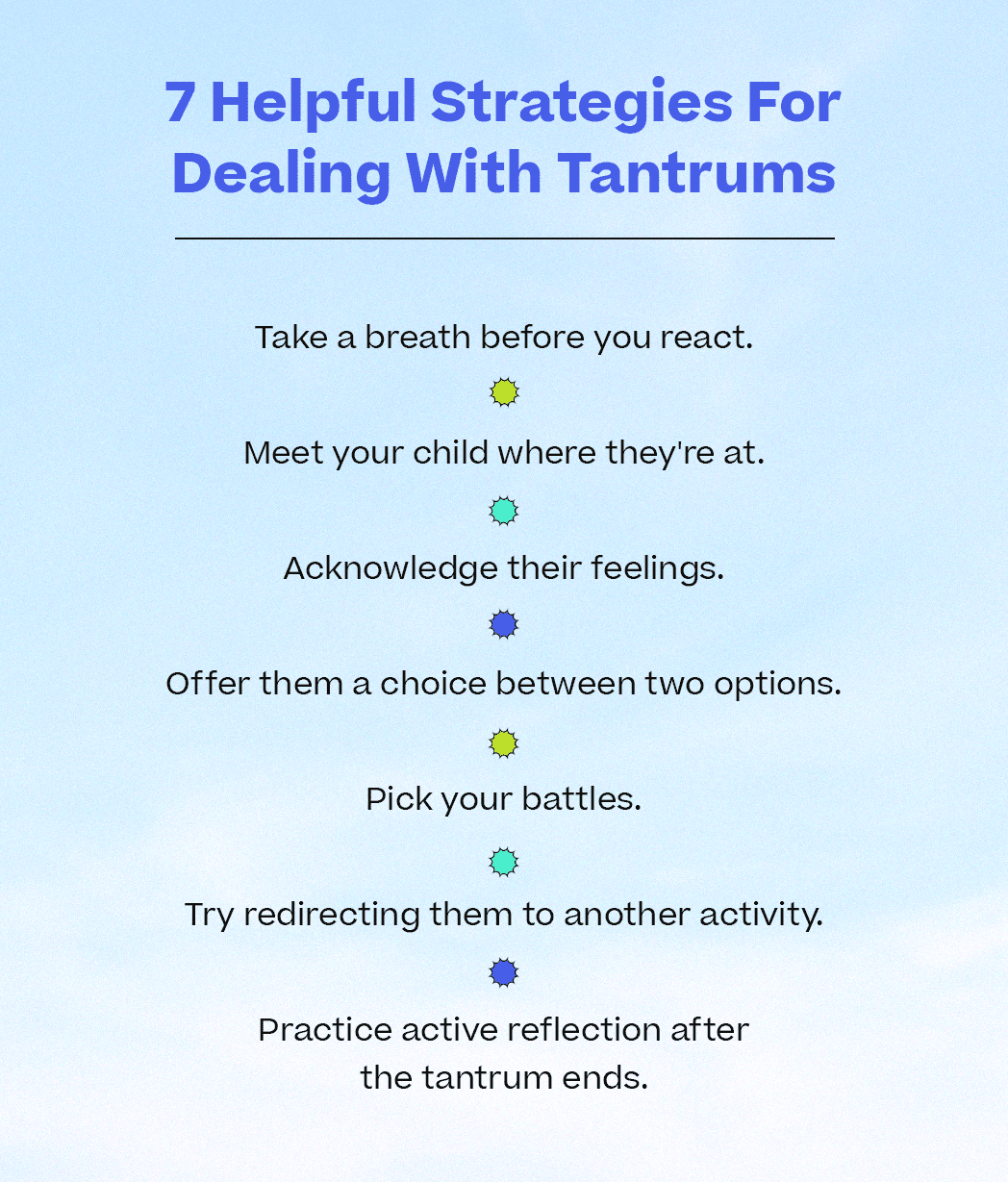

When your child throws themself into a tantrum, Dr. Pederson recommends parents first take a second to assess the situation. If you're in public, you most likely have to deal with the tantrum right there, right then — but if you're at home, you have a second to assess how you want to respond. Either way, Dr. Pederson encourages parents to pause and take a deep breath before responding.

Next, meet the child where they are physically. For example, if she is in the grocery store when her daughter begins melting down, Dr. Pederson says, she tries to crouch down to her eye level to speak to her, instead of yelling at her from above. "I really like giving toddlers choices so that they can save face," she explains. "Sometimes the toddler might agree to be held and to get through the checkout line. Sometimes you do have to say, 'Hey, I'm going to leave my cart here. We'll be back in 10 minutes. Let me just take care of this.'"

Dr. Pederson also says it's important to acknowledge what's happening. Help your child name their feelings by saying something like, "You feel pretty frustrated right now, don't you?" or "Yeah, this line is taking a long time, isn't it?" That said, Dr. Pederson says it's important to refrain from lecturing. "A tantrum is not a teachable moment. It's not the time to lecture," she says. "It is not the time to explain to them why they can't have sugary things at lunch every day. In the moment, you just want to recognize what's going on. Acknowledge how they're feeling, and calm things down."

In the moment, you can also help your child find ways to calm down. Try asking them to close their eyes and take big belly breaths or redirecting them to a different activity if you're at home. Sometimes, encouraging them to take a break will help them relax and let go of the tantrum. Dr. Pederson suggests parents avoid saying no during the tantrum, as it can only make your child more upset, and avoiding corporal punishment. In general, she recommends taking a hands-off approach unless you have to restrain your child to prevent them from hurting themself.

Once the tantrum ends, it's time to reflect on the situation. Start by going back to basics, Dr. Pederson says: "Are we sleeping well? Is our nutrition good? Do we have stressors in our life? Are we getting enough physical activity?" A disruption to any of those categories could be causing tantrums.

Dr. Pederson also recommends looking for patterns in your child's tantrums. If they have a breakdown every time you take them shopping, maybe try ordering groceries for pickup instead. "Is there anything about today that was a little bit hard for her? Is there a way that I could have handled this better? Try to share those active reflections with your children so that they can learn those habits, too," she says. In her household, the issue was ice cream: her daughter became obsessed with it and wanted it for every meal, so Dr. Pederson had to stop buying it for a month or so until the phase passed. "She knew it was in the freezer," she says, laughing.

The hours after a tantrum are also a good time to have a conversation with your child about what happened. Dr. Pederson says toddlers will often replay a conflict after it occurs, either in pretend play or with friends, to try to understand what happened. As a parent, you can also encourage that emotional growth by asking them to talk about what they were feeling and what happened and letting them know it's OK to have a hard time.

That conversation is also a perfect time to reflect on your own behavior. Maybe you yelled at them instead of responding calmly or you had missed their nap time and now feel bad about it. Dr. Pederson says showing your child what active reflection — and even a genuine apology — looks like can be a powerful thing. "I have a 2-and-a-half-year-old, so I'm in the tantrum phase. I have to apologize to my daughter sometimes," she says. "We want to teach children how to deal with their emotions and regulate their emotions. One of the best ways to do that is by naming emotions and working through them, both for them and for you. None of us are perfect, and I think those are really good ways of providing an example for them to follow."

Although tantrums are a universal experience for toddlers, speech or developmental delays can lead to more severe meltdowns. "Not being understood is a very common cause for a tantrum," Dr. Pederson says. "I often find that when children are old enough to articulate, 'I'm mad, Mommy. I wanted my blue cup,' then they have a lot less physical symptoms of the tantrum because they're able to articulate that." If you notice your child is having especially severe tantrums or still experiences them over the age of 4, Dr. Pederson suggests reaching out to your pediatrician for help. "It's never the wrong decision to talk to your pediatrician about it," she says.

Dr. Pederson says it's also important to remember that tantrums are a normal, even healthy part of growing up. "They're inevitable, and you just have to weather the storm. You want to do it in a way that feels good to you, and you want to do it in a way that respects your child so that they can, over time, learn how to help regulate their emotions," she says. "It's our role as parents to set boundaries and guidelines for them to develop into a functioning human being that can be part of society. . . . We have to remember that these are real emotions that the children are having, and we have to be adaptable and flexible."

There is a light at the end of the tunnel: over time, your child will grow out of the tantrum phase. Recently, Dr. Pederson has begun to see a glimmer of hope in her own daughter's behavior. "What's so fascinating to me is my daughter's finally at the age now where she'll still have her tantrums, but maybe an hour or two later, every once in a while, she'll be like, 'Mommy, I'm sorry that I threw the book today,'" she says. "I'm already seeing her learn that emotional regulation and recognition and understanding how we impact each other.

For more tips on raising happy and healthy children, visit stanfordchildrens.org.

Design: Kelly Millington