Black Men Reflect on bell hooks and Her Work

A Thank You to bell hooks — From Black Men

One cornerstone of bell hooks's work was that patriarchal ideals harm both men and women. In her 2004 book The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity and Love, hooks points out how societal expectations regarding masculinity can have distressing effects on boys: "To indoctrinate boys into the rules of patriarchy, we force them to feel pain and to deny their feelings." To fulfill the ideals of sexism, hooks noted that boys are rewarded for "acts of soul murder."

Speaking more directly to the Black plight in We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity, hooks examines how racism helped to form societal expectations for Black men: "Within neo-colonial white supremacist capitalist patriarchy, the black male body continues to be perceived as an embodiment of bestial, violent, penis-as-weapon hypermasculine assertion." She lamented that as Black people in a white supremacist society, we were taught to shun vulnerability as a means to survive — namely because that keeps us from love.

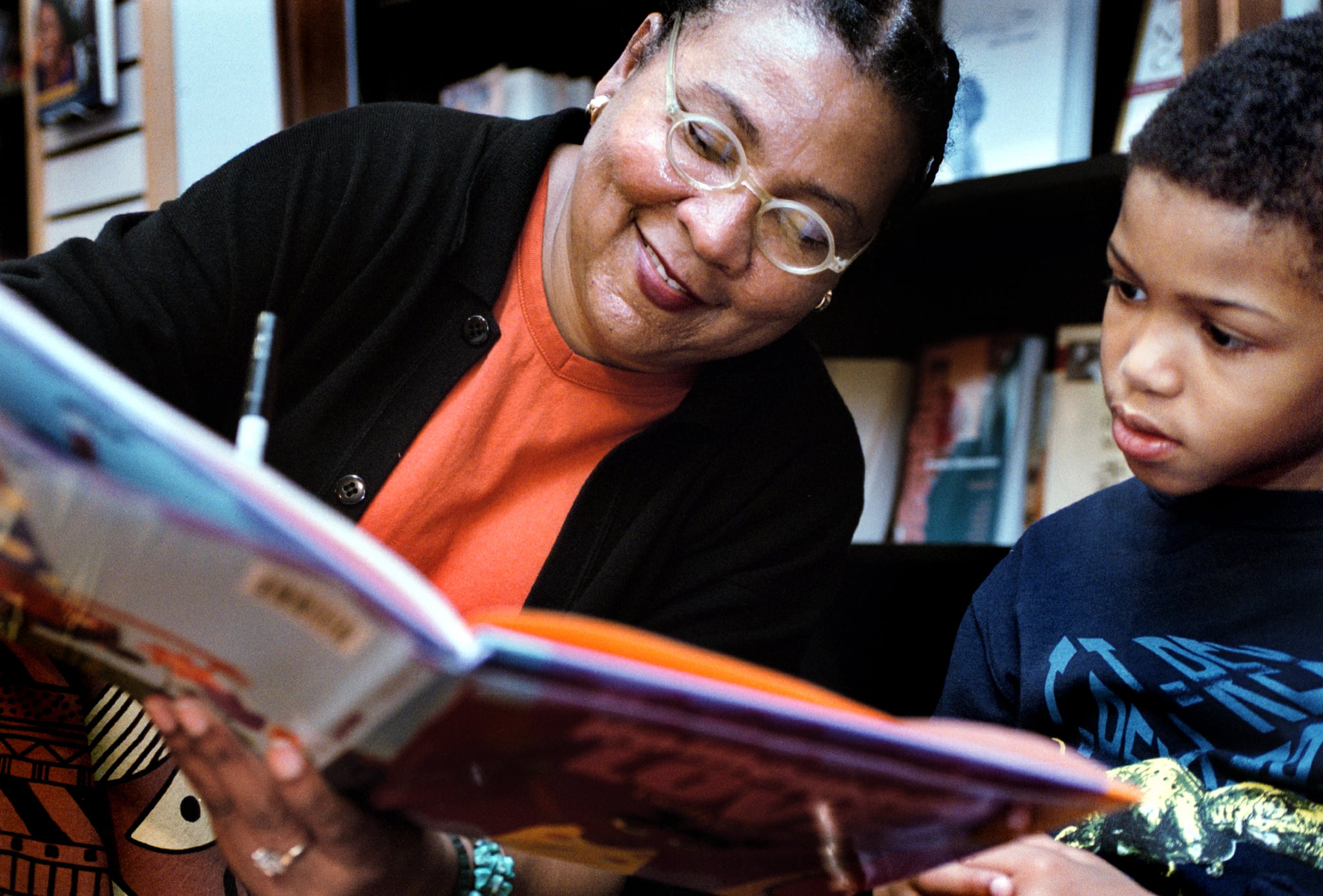

hooks was long a champion of Black men's ability to be tender and free. I've personally witnessed them be validated by her acknowledgement of their pain and preciousness. As we continue to honor her life and work, I thought it would be fitting for Black men to lay roses at her feet.

"When we can see ourselves as we truly are and accept ourselves, we build the necessary foundation for self-love" — bell hooks

Who was not made better by bell? Brought to tears, brought to a well, and made to drink? bell hooks by herself is a whole language. The first time I read her I had to not only reread her but reread myself; relearn and unlearn myself and what masculinity meant. We cling to things that serve us. bell was teaching us how to not suffer under the guise of patriarchy in a way that was terrifyingly healing, bound to a beauty that was not beholden to white feminism as the lens through which we see ourselves. bell was not to be played with. bell was freeing all of us. bell was breathing and living for all of us.

When I think of bell I also think of Toni Morrison; I also think of Angela Davis. I think of the Black women who sheltered and carried our burdens for us. We did not ask them to. When I think of bell hooks I think of Tricia Hersey of The Nap Ministry and this idea of rest and restoration; of reparations owed and the toll of being a Black woman in America takes on the mind, body, and spirit. And how a woman's work, a Black woman's worth, is as much tied to the diasporic ways we see ourselves: in every word, every nook of a book and bending of a continent to the whims of colonialism, we can also see the freedom that bell was calling us to strive for. In bell hooks we can see the path to liberation so clearly laid out, clean, and bare for us to dive into.

When I think of bell I think of Audre Lorde; I think of Sonia Sanchez and Nikki Giovanni. I think of the lineage of griots, of writers, who have told us about ourselves masterfully. I think of the exposed wounds they afforded us the opportunity to bear witness to. I think of Ida B. Wells, of Kimberlé Crenshaw, of Kathleen Cleaver; I think of Black women pushing against the grain, making us question over and over again the hows and whys of Blackness and the totality of that experience and how it gets to show up against the backdrop of a white world that would rather see us suffer than strive. My friend Zola Ellen talks of world-building: this idea that we can create these ecosystems in which we can find freedom. bell hooks, by herself, was a whole planet — a human feeding us, freeing us, giving us light and love and the in-betweens that were as messy as we needed them to be.

When I think of bell hooks I think of love — a gut-wrenching, soul-stirring, chin-checking love. The kind of love for self and people that can rewrite, reshape, and reexamine the history of a people . . . our people. When I think of bell hooks I think of a mirror being held ever so rightly toward a better future, a mirror held up to each other, a reflection of a language that we will spend years unpacking. bell hooks allowed us to feel free in our expressions of Blackness, of love, shifting power dynamics in a way that was both palatable and also emboldening. bell never pandered, never withered in her stance. bell never made us feel smaller. We were greater than any sum of the parts whiteness wanted to give us because of bell. We were giants because of bell.

Our work, our world, our people — we were and are all made better, today and every day after, because of bell. — Joél Leon"When I think of bell hooks I think of love — a gut-wrenching, soul-stirring, chin-checking love." — Joél Leon

I was first introduced to bell hooks in the fall of 2011 during a course on feminist jurisprudence. During my master of laws program at American University Washington College of Law, studying Gender and Law, professor Ann Shalleck wanted to challenge me and my peers on our thinking of feminism as a theory only made available to and for wealthier white women. What started by having us read Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center and Feminism Is For Everybody: Passionate Politics turned into my lifetime of commitment to hooks's work, becoming a better person, and seeking the truth to hard questions about race, gender, sexuality, class, and socioeconomics.

In my studies, then later in my personal and professional life, hooks became a perfect example, a North Star for many of us, of what it meant to center the most marginalized communities, the very praxis I find important in advocacy work. Even while committed to the academy, hooks deeply understood that the vast majority of the people who needed the information about feminism and feminist theory weren't always (or usually) in academic spaces. In her writing, hooks made feminism accessible to everyone and worked to subvert it from being something only white women could access.

In her writing and speaking, hooks allowed us to lean into hope and love — and forced us to recognize that those acts were just as radical, too. I first learned this in her groundbreaking 2000 book All About Love: New Visions, where hooks challenged our daily notions of what it means to give and receive love, and how that reality, even when distorted, is often shaped by our early adolescence. It has since allowed me to learn and relearn care, commitment, compassion, open communication, and vulnerability. And, conversely, it forced me to reckon with unlearning patriarchy and manipulation.

As a Black queer man, never did I feel a deeper connection to hooks than in her 2003 book, We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity. In it, she writes: "In patriarchal culture, all males learn a role that restricts and confines. When race and class enter the picture, along with patriarchy, then [B]lack males endure the worst impositions of gendered masculine patriarchal identity." For hooks, she knew that many Black men are forced to repress themselves in an America centered on whiteness and white supremacy. And when compounded with racist and sexist attitudes, Black men, especially those who are willing to subvert these systems, become criminalized and dehumanized.

Sixty-nine years old is young. It should not be normal for our elders to now be ancestors at this age. But if hooks must rest, let it be in perfect peace, understanding that we indeed paid attention to the substance of her work, not who she is — though that also happened to be incredible, too. — Preston D. Mitchum, Esq., LL.M.

"She wrote to me and men and boys like me, understanding that, for better or worse, the stewardship of vile patriarchy was in our hands." — Andrew Ricketts

The right way to honor bell hooks is to love better. But now, the prime examples of that love — her unending physical devotion to teaching, her sonorous voice, her river of words — have left the physical world. So I have to cite her. She is the "ancestor" I must cite in these sayings about our hopes and dreams. She is the reason we now call the unheralded tasks of parents and caregivers "emotional labor." She is the source of our newly popular critique of capitalism, where we occupy stations of resistance and skepticism in the name of a deeper, more humane love. A love without a gaudy price tag. She is the reason we realize that rest is love. We cannot forget her just because the results of her work have become so pervasive that it feels like the air we breathe. I cannot forget that it is my time to carry on those principles so that she, too, can finally rest.

But I'd be lying if I said I was on the side of love and not violence. That line in the sand, between the actions that demonstrate love and the ones that destroy it, is also what divides men from the subjects of our abuse. I am still too often violent, abusive, and uncaring. Maybe less so because of bell hooks's works like All About Love. She wrote to me and men and boys like me, understanding that, for better or worse, the stewardship of vile patriarchy was in our hands. She understood that we would sooner implode than give up the idea of control. That's what she was up against.

I will cite her here to pledge myself to the women in my life that I say I love, that I mean to love, but who haven't gotten enough or any of that humane devotion that bell hooks taught. In a talk at the University of Washington in 2006, she made it plain:

"Every female wants to be loved by a male. Every woman wants to love and be loved by the males in her life. Whether gay or straight, bisexual or celibate, she wants to feel the love of father, grandfather, uncle, male partner or son. Think about all the lesbians that are having sons. They want them to be males that they can love from childhood into adulthood. We live in a culture where emotionally-starved, deprived females are desperately seeking male love."

As I write, I know my mother craves more of my love. I've left her to grieve her late husband, late father, and late uncle in relative isolation. The emotional labor that my aunties have always bore remains with them as the men in my family, predictably, die off and disappear — traces of their love wisping into the ether before anyone can grasp. As I write, I know my romantic loves crave more of my commitment. Not just during pillow talk and celebration but through hardship and anger, through the bitter moments of my own neglect. So I am renewing my commitment to a love that listens, to a love that submits, to a love that molds itself around a community and within it. I'm renewing my commitment to my best teacher, knowing that her name was synonymous with the loving practice she left behind. — Andrew Ricketts

"hooks became a perfect example, a North Star for many of us, of what it meant to center the most marginalized communities . . . " — Preston D. Mitchum, Esq., LL.M.

I dove into bell hooks's All About Love the day after finishing eight months of pandemic-flavored virtual grief and loss workshops for a union of healthcare workers.

I had been carrying hundreds of devastating stories of loss that I'd tried to convince myself were "just informational." I had only begun to acknowledge the impact those stories had on my body and spirit after my mom reminded me that they weren't. I was 10 months into my first solo Brooklyn apartment, working to rebuild and love myself after years of raggedy mental health, homelessness, and its crushing dehumanizations.

I felt numb and disconnected from my emotions often, but when bell hooks sang my life with her fears of a younger generation that sought pleasure without intimacy "so fearful of the pain of disappointment that they will forgo the possibilities of love and joy," she had me texting and posting excerpts with the fervor of the freshly evangelized.

The night after I gasped, highlighted, and annotated my way through the first few chapters of All About Love on my stoop, I called a handful of wise friends in unstabby unions to ask questions like, "How did you know you were in love?" and "How did you learn about love?" and "OK, yeah, but, like, what did it feel like?"

My reading of hooks's work resulted in pages and pages of impassioned headlined and illustrated journaling, multicolored highlighting, and poll notes. In retrospect, I was a person in love, but immobilized by fear, shame, and the inability to believe that I was worth loving in return. I felt both cared for and attacked when bell swerved over into the foundations of self-love. The raggedy self-regard neutralizing my attempts to give and receive love were being underlined, bolded, and italicized.

bell hooks laid bare how unhealed wounds, extinguished passions, and dances with love and lovelessness can shape, color, deepen, sustain, and ease our pains. I felt hopeful as she explained how "the intensity of our woundedness often leads to a closing of the heart." She lovingly cautioned against expecting received love to fill in your cracks, and noted that the knowing and the naming of things were but a piece of the work.

I read her chapter on community the day after facilitating a literary therapy writing session around grief and being able to gauge post-traumatic growth. I closed the book and took a walk around the block, letting tears fall after bell reminded me that "rarely, if ever, are any of us healed in isolation. Healing is an act of communion." I hadn't realized how vital the fellowship, safety, and welcomed vulnerability in those spaces were in extending grace to myself and not letting my murderous Inner Hater win. I needed that cry.

As grief unfurls and gratitude pours out after this massive loss, I'm finding comfort in seeing how many others this genius saved and freed with her charge to remember that abuse can't coexist with love, and to appreciate all parts of ourselves regardless of how the world responds to them.

Thank you, bell. — Alexander Hardy