What It Was Like to Live in the Ecuadorian Rainforest

A few years back, I traveled to Ecuador to live with an indigenous community for three months in the region of Napo. It wasn't until then that I truly realized how much knowledge and wisdom these communities pass on through generations. I've always been interested in getting to know different cultures, fully immersing myself and living them to an extent that you are only able to do when adapting to their lives pretty much close to 100 percent. Ecuador's El Oriente borders Peru and Colombia and bursts with lush green rainforests, insects three times the size we know them to be, exotic plants, picturesque flowers, rivers, waterfalls, and unimaginably tall trees, which grew up to 60 meters high. It is hard for me to describe its fascinating beauty and energy.

From left: Hanno, Brett

From left: Chris, Mike, Hanno

Arriving in Ecuador was a little disaster to begin with. My flight from Venezuela to Quito was canceled. I spent my first night in Caracas, not knowing much Spanish and being completely lost at the airport. My phone, of course, did not work. I connected with some strangers who, as well, looked confused and lost. They were on the same flight and spent their night at the same hotel. What a lucky girl I was. So here I was, alone in Caracas, having dinner with complete strangers who became my friends, with whom I am still in touch and met up with numerous times over the past few years: Hanno, Brett, Chris, Mike, and Tomas, a film crew from Berlin who traveled to Ecuador to film a documentary about indigenous communities.

Before I began my own journey into Ecuador's Oriente, we traveled through Quito together, explored the city, and enjoyed its delicious and simple food. What an energetic, lively, and colorful city. It was a strange feeling to say goodbye to the people who you've known for only two weeks but whom you share an experience with that is hard to put into words.

Quito, Ecuador's capital

And this is where my own journey began. I arrived at a remote bus stop, two hours from Tena, the capital of the province of Napo and six hours from Quito, Ecuador's capital. I waited until I was picked up by Oswaldo, one of the indigenous group members. Time as we know it doesn't really exist there. Waiting for hours on end, not having a set schedule is normal, something I struggled with quite a bit. Oswaldo's family is Quechua, direct descendants of the Incas. I never really learned Spanish in school, so I prepared with a few private Spanish lessons before I began my journey. I honestly felt unprepared and somewhat naive. I couldn't properly communicate and felt that I was disrespecting their hospitality by my lack of communication skills. I didn't speak one word of Quechua. Who could have known? Quechua is the language of the Inca empire and is completely different from Spanish. One-third of the Quechua people don't speak Spanish, and then there was me, a tourist, who barely spoke Spanish and couldn't bring out one word in Quechua. I wore rain boots and cotton pants, the worst decision I could have made. The humidity and heat in the rainforest was often unbearable. Within only 30 minutes of marching through the rainforest, my pants were soaking wet. The humidity throughout the entire year is about 95 to 100 percent.

The daily dose of fog.

I was given a machete upon meeting Oswaldo, not for defending myself from potential predators, but rather for freeing our path from plants and roots that were in the way. After each rainfall it felt like the path we just freed was completely overgrown again. It took me some time to get used to passing people with machetes and, sometimes, guns. Again, adapting to their lifestyle without judgement was important to me. It still fascinates me how well Oswaldo knew his way to the camp through pathless and rough areas of completely overgrown areas. We had to cross a riverbed to get to the other side; what an interesting and challenging landscape I was allowed to experience along the way. Once we arrived I was exhausted and didn't know yet what situation I put myself into. My home for the next few weeks was a beautiful wooden cabin built on stilts, right next to a little riverbed. The shelters and houses Oswaldo and other men from the group built were modern and had everything you really needed, a bed, and a couple shelves. I believe a lot of us often have the idea or imagination of indigenous communities living a primitive life, but that is a wrong belief to have. Living a simple life can have a lot more meaning than a lifestyle most of us are used to. Materialism is a concept that has the opposite effect on what it means to take advantage of the resources given to you and learning how to use them to your advantage. I do believe there is a lot of pressure these communities are exposed to to adapt to a more globalized lifestyle.

The Amazon at night.

It took me a long time to adjust to the food, not having electricity, no reception, no potable running water. At night, candles were my only source of light and I was hoping they would burn throughout the entire night; I was afraid to sleep in the dark — the noises were overwhelming and I had a hard time relaxing. It was hard on me not being able to truly communicate with anyone. I spent a lot of my time being with myself and my thoughts in the middle of nowhere. It was challenging, as I thrive being around people I can have deep and intimate conversations with. Sitting by the river, listening to the birds, and watching the trees for hours on end became a normal daily routine. It is difficult to summarize such a transformational trip into a few words as well as remembering all the magnificent experiences I have made. I often wish I brought a diary with me.

Ecuador's Oriente has a high biodiversity and is home to numerous endemic and endangered species that need to be protected.

One night an elder of the tribe offered me to try ayahuasca, something I have researched and heard of a lot of times before but declined politely. Something I was and still am afraid of, losing control of my body is something that gives me chills. Ayahuasca is a hallucinogen that is used for clarity and connecting with yourself and the spirit realm. Trying such a kind of hallucinogen, you need to feel safe and comfortable wherever you are, and I wasn't mentally there yet; the depths and unknown of the rainforest frightened me. I feel hesitant toward any types of drugs and it was difficult for me to accept help when I got sick. It happened about four weeks in and I thought the painkillers I brought, preventive shots I got, and antimalaria drugs I took prior to the trip were enough, but they weren't. I had horrible cramps and had to deal with all sorts of symptoms from having food poisoning. The elder of the tribe insisted on helping me and brewed a dark green drink out of plants from the forest. It all sounds straight out of a movie, doesn't it? He folded a big green leaf in half to create a funnel, which he held onto my nostril, one for one, and poured lime juice straight through my nose into my throat. What an unpleasant and painful sensation — to this day I don't know what plants he used, but I felt better every day. What a fascinating and spiritual treasure to have such deep knowledge of healing plants and using the resources provided by your land.

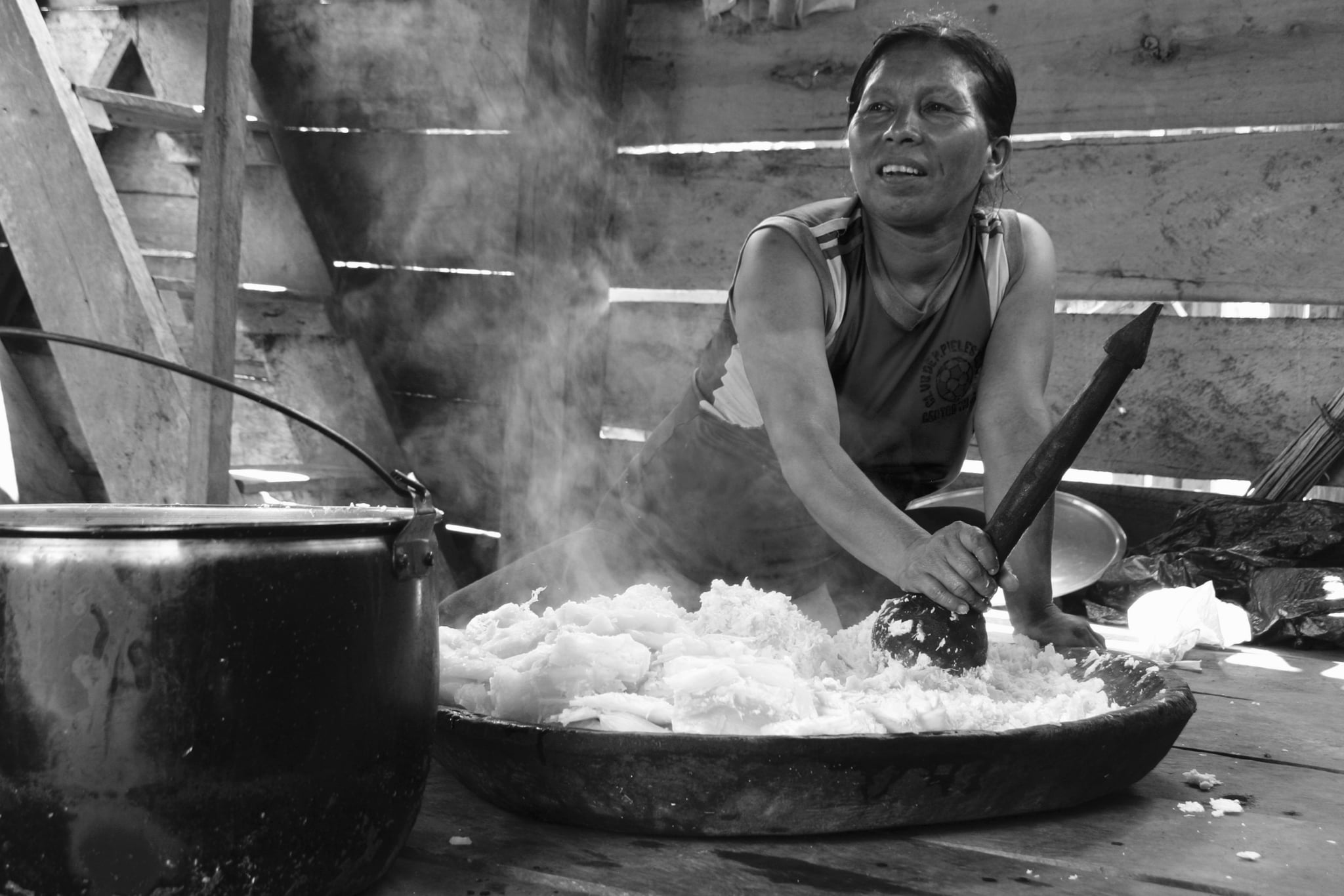

Throughout my time in the Oriente, we went to Tena once to purchase food. What an exciting day! I remember eating two Magnum ice cream bars at once. My craving for sugar was bad. I bought two packs of cane sugar to take back with me to eat with a spoon to keep me happy and content. Two to three spoons per day it was. The only happy drug that didn't melt in the bursting heat. Half a day later and back at the camp, the next few weeks began. I learned a lot about myself. I slowly started to adjust and be OK with the solitude I was exposed to. The more I relaxed, the more I could see the beauty that surrounded me and I felt like that was exactly where I belonged at that time. Before I go on, meet Oswaldo, his wife, and kids, Irma, Brian, and Kerli.

Natural mosquito repellent (on the right).

Cascada de San Rafael

I remember one morning Oswaldo took me on a hike deep into the rainforest. He hiked in front of me and asked me to keep about two meters distance from him. He abruptly stopped in the middle of our hike and suggested with a hand motion for me to not move. He took his machete and slid it through something in the tree right in front of him, and then it fell to the ground. It was a baby snake. I wish I remembered the name of the snake. It was very poisonous, that's all I could remember. I don't know if I truly realized in the moment how dangerous the situation was. I've heard young snakes are more venomous than adult snakes because they don't know how to control the venom they inject when they bite. Being bit in the middle of nowhere can be an unfortunate way to go, but let's move on to what happens next!

We arrived at a small plateau, which was overgrown by bushes and vines. In the midst of all that tangle were a few bigger boulders. Oswaldo brushed off some leaves and undergrowth from the boulder and there it was: engravings from ancient Mayans. How magical. How unthinkable. How incredible. A secret so well kept that in the world I could not find this location again. Indigenous people deeply understand the land that they lived on. Oswaldo's sense of direction was incredible and it more and more showed me that we humans are capable of so much more than we think. Using our Google Maps navigation is so easy, buying medication from the drugstore is so easy, buying a frozen meal from the supermarket or buying fresh vegetables seems so brainlessly easy. What if we only try to use the resources we have, try to learn to understand and use them, and let our intuition guide us? What if we try to learn more about our surroundings, the food we eat, how to harvest, and how to live with only things we truly need? Neglecting our instinctual senses will possibly transform us into robots rather sooner than later. Preserving the knowledge and secrets that kept our ancestors healthy, wise, and strong is something we should put more focus on, but I understand that evolving into a direction where technology plays a major role in our lives is a natural progress of evolutional knowledge and us humans.

The Base of Reventador

My next adventure was climbing to the base of Reventador, an active volcano that lies in the eastern Andes of Ecuador. I booked a room in a hotel near the starting route and met three fellow travelers who planned on climbing Reventador as well. It was a relief for me to be able to communicate again and be understood. So here I was with my new acquaintances heading out for a day hike. At the time I visited, there were no trail posts, nor any other signage of showing you where to go. All we had was a map and a GPS. I wish I could remember more details in depth, but it was a painful, steep, but beautiful hike into Ecuador's cloud forests. Upon arriving at the base of the volcano you could see a vast landscape of fault lines and dry lava rock fragments, partially covered with moss and wild flowers. Its magical appearance is hard to describe. The hike back down was adventurous as well. It started pouring, a rainfall I haven't experienced to such extent. The steep trail was now a small rushing waterfall. Slipping was inevitable and the rain cover for my backpack didn't keep anything dry. Hiking back to the hotel, we walked through a small town at the feet of the volcano. A big oil company had built a giant pipe through the town; the smell was extremely strong and watching people dry their clothes on the pipe was saddening and angering at the same time. Ecuador is a beautiful country that I hope will survive the movement of deforestation and pollution of its rainforests through the oil industry. Its remaining natural resources are too precious and valuable to risk culturally, spiritually and ecologically.

Ecuador was an eye-opening journey, a trip that taught me a lot about myself, confronted me with my fears and limiting beliefs, and is something I will remember fondly for the rest of my life. I'm grateful to have met such beautiful and genuine souls. People who adopted me as part of their community, who provided me with food from their land, water from their rivers, who taught me about their plants, shared secrets with me and offered genuine care from their hearts. These people are people we all should look up to, people who appreciate and embrace a simple life and share everything they have with a stranger from a different world who doesn't even speak their language.

Image Source: POPSUGAR Photography / Julia Sievert