Feeling Like You Don't Always Belong in Your Race

What It's Like to Feel Stuck in Racial Limbo

Marina Liao, Assistant Fashion Editor

As I grew older, however, I understood that not feeling "Chinese enough" or "white enough" is not just about missed cultural nuances and holidays. It has to do with the environment you grow up in, the people you surround yourself with, and a host of other circumstances that shape a person. I realize how lucky I am to have a diverse group of friends to this day, including my Asian sorority sisters from college. It's taught me to be comfortable around all types of people and to respect everyone's culture or religion, even if it is not what I choose to believe in. When I hear some of my sorority sisters say they regret not going outside of the "Asian group" to meet more diverse people, I can proudly say, "Sorry, but I don't have that problem."

Because I appreciate both American and Chinese culture, I don't feel the need to choose just one. Though in the end, I still don't know how to quite respond or feel when someone calls me whitewashed. Do they want me to say thank you or be offended? Between being called really white and an ABC, I guess I'm just a really white American-born Chinese person in other people's eyes — and because of how that's shaped me, I'm OK with it.

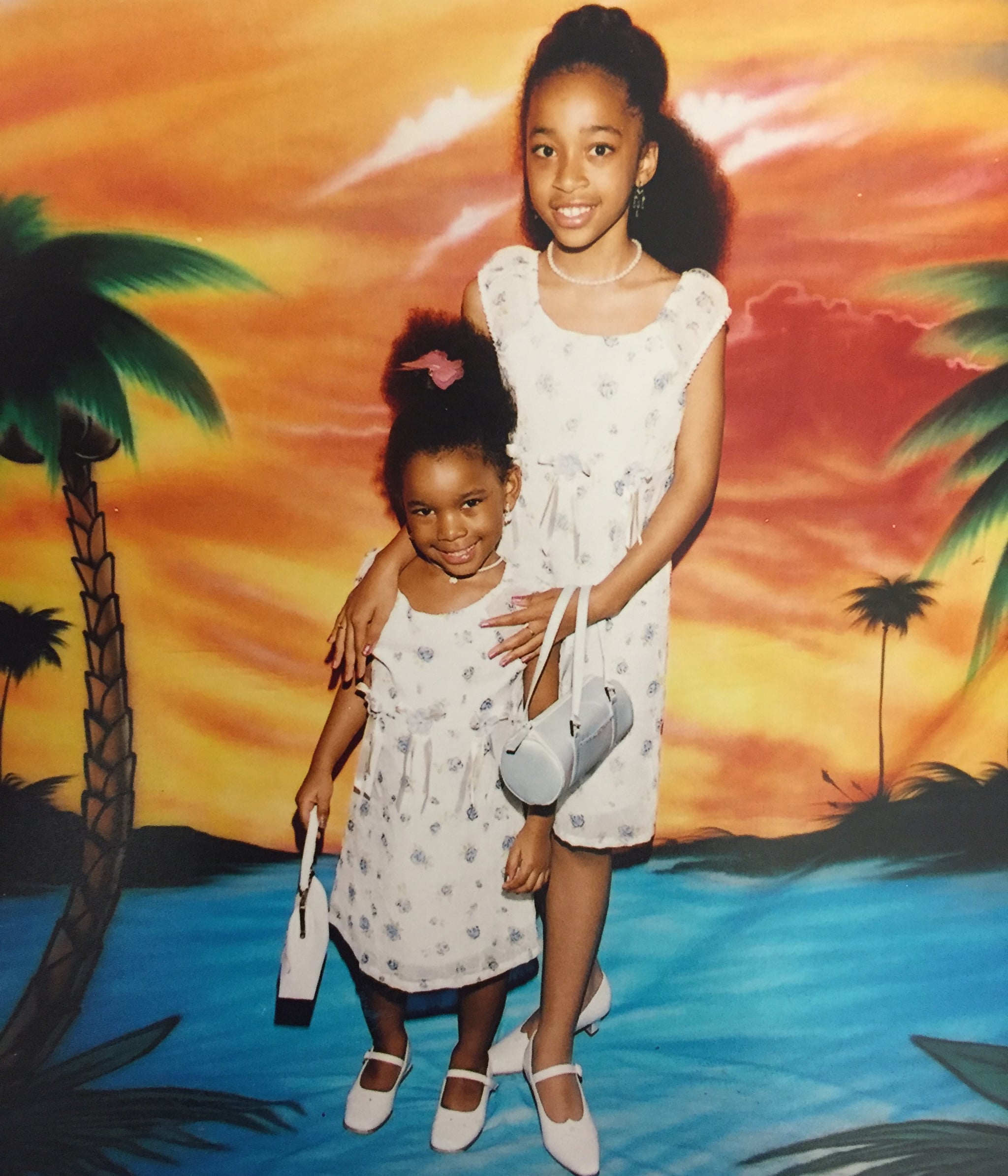

Aimee Simeon, Assistant Social Editor

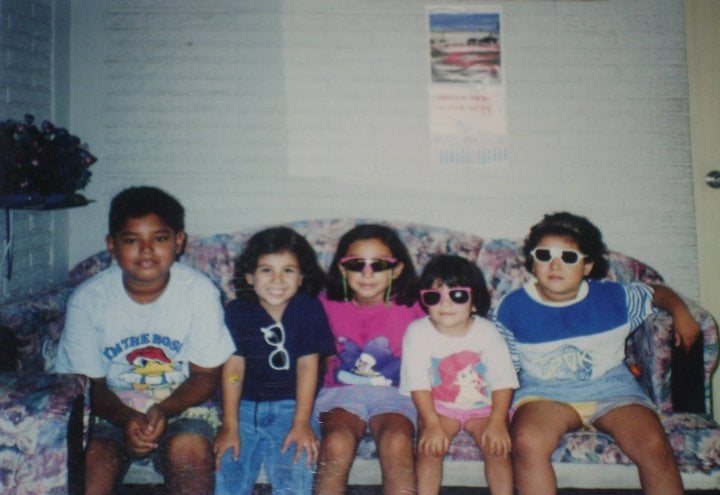

Lisette Mejia, News Editor

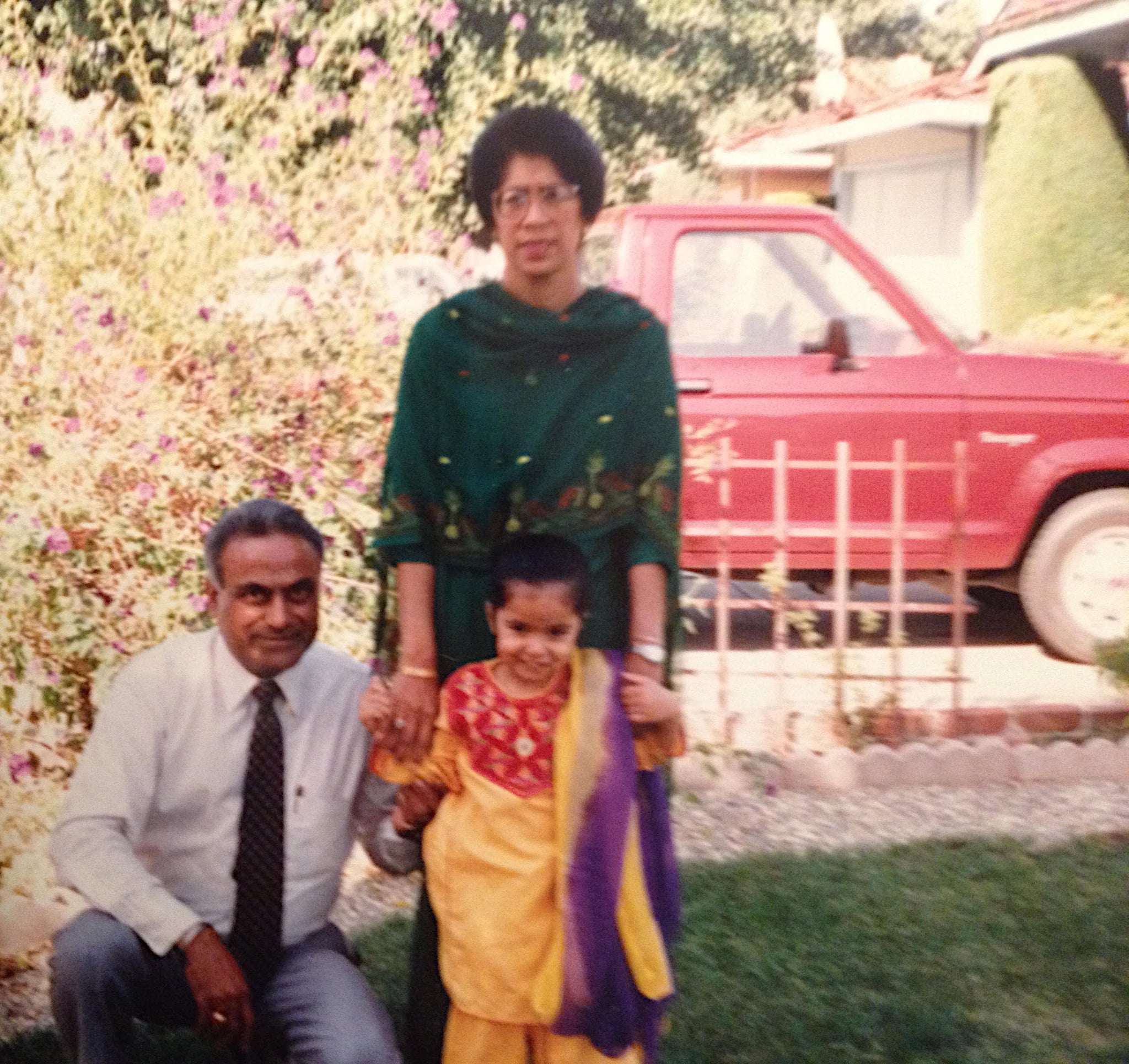

Sabrina Dhillon, Former Video Audience Development Manager