How Do Asian-Americans Fit Into the Fight Against Racism?

What It's Like Being Asian-American and Feeling Left Out of the Race Conversation

During my junior year of high school, my friend Anna invited me on a student trip to New York City. The trip would be focused on a United Nations summit on globalization and peace, organized through a nonprofit foundation called Eracism. "What a clever name," I thought, before agreeing to go. However, what transpired on the trip did not erase racism; instead, it managed to erase any remaining shred of confidence I had in my own racial identity.

Revelers celebrate the start of the Chinese New Year on February 19, 2015, in New York City.

A few days into the trip — during which we visited the tenements of New York City's Lower East Side and met with various religious groups — our group found itself in Chinatown, on the famous Canal Street. While we were waiting to go to our destination, I heard one member of the Eracism group say to another, not in a hushed voice, "Don't tell anyone this, but I don't like Chinese people." The recipient of this indisputably racist statement was an Indian kid, who responded with, "But you like Indian people, right?" "Yeah, I don't mind Indian people." "OK, cool."

This was quite literally the most ironic statement anyone could ever utter on a trip for Eracism, whose very mission was to raise awareness about prejudiced attitudes like this.

To say I was sent reeling into an out-of-body experience is an understatement. After years of enduring countless instances of racism, including physical assault, this exchange on the Eracism trip was the final blow to my self-confidence and self-identity, and it would take years for me to recover. To this day, my chest still feels heavy when I think of that instance.

The Invisible Race

Given the egregious lack of awareness of being racist against Asians on a trip aimed at fighting racism, it's no wonder that many scholars and Asian-American identity experts have referred to Asian-Americans as "the invisible race." David Haekwon Kim, associate professor of philosophy and the director of the Global Humanities initiative at the University of San Francisco, told The New York Times: "I believe the invisibility of Asian-Americans in our culture has been so deep and enduring that Asian-Americans themselves are often ambivalent about how they would like to see themselves portrayed and perhaps even uncomfortable about being portrayed at all."

It seems Asian-Americans just want to stay above the fray. Being a minority already poses its challenges, but what's particularly disheartening is that oftentimes, Asian-Americans are made to feel like an other among the other, and sometimes among ourselves. I first realized this on that unforgettable trip to New York.

I was born in Wuhan, China, and moved to the US when I was 5. At that age, I had barely formed any sense of my own personality, let alone my racial identity in the context of an increasingly globalized world. My entire existence revolved around my favorite time of day, when Journey to the West came on TV after dinner, and my most loathed activity, nap time. I was never old enough to become cognizant of the privilege of belonging to the majority race. For my entire life, I have only been aware of being other.

"They're fine. They're doctors and engineers. What do they have to worry about?" That would be a gross reduction of the Asian-American experience.

Before we go any further, let's examine our country's current social climate around race issues. A tall order, I know, but an increasingly urgent one, as the 2016 election cycle hurtles potentially toward a new chapter of unprecedented bigotry, and as one particular racial group remains palpably absent from the conversation.

As both history and current events illustrate, the black community continues to face widespread racism in the US. Whether it's the shootings by law enforcement, examples of which are both steady and steadily disturbing, or institutional discrimination in jobs as varied as fast-food worker and airline pilot, these incidents reflect a deep-seated prejudice that continues to tarnish this country's integrity.

However, something positive has risen out of this relentless demoralization and plundering of the human spirit. The Black Lives Matter movement has reinvigorated a campaign for change that had quieted in preceding decades but never waned. Now Black Lives Matter is starting to gel into more than just a hashtag-backed movement; it's evolving into a political platform aiming to enact change through lobbying Congress.

At the same time, Muslim-Americans face increasing discrimination driven by Islamophobia, which stems from fear of the Islamic religion but which many scholars consider to be a form of racism. It's a hateful sentiment that flares up each time divisive figures like Donald Trump react to tragic acts of terrorism with incendiary rhetoric. Most notably, Trump has proposed a temporary ban on all Muslims entering the US, which a poll from March found that 50 percent of Americans supported.

Muslim-Americans aren't the only group in Trump's crosshairs. The very utterance of Trump's name conjures an expansive, hulking wall across the country's southern border. Astoundingly, when the Republican nominee reduced all Mexicans — and later, all Latinos and Middle Easterners — to criminals and "rapists" during his candidacy announcement last June, the crowd did not boo him off stage, nor did the country react by squashing any real chance of a campaign. Instead, much of America cheered his blatant bigotry, allowing Trump's remarks to set the tone for what has become a campaign fueled by hate and divisiveness.

The society we live in today is largely defined by its racial progress. While it's alarming to see the effects of systemic racism in certain communities and Trump's new brand of accepted bigotry take shape, it's also heartening to see Americans fighting with unprecedented rigor to stand with the black community, to stand with Muslim-Americans, to stand with the Latino population . . .

But wait a minute: what about Asian-Americans?

According to the United States Census Bureau, there were just under 21 million Asian-Americans in the US as of July 2015. That's roughly 6.5 percent of the US population, making us the country's third-largest minority group behind Hispanic Americans (17.6 percent) and black Americans (13.3 percent). In fact, Asian-Americans have been the fastest-growing minority group in the US for more than a decade, increasing in population size by 56 percent between 2000 and 2013.

But where are the movements advocating for Asian-American rights? Is it because Asian-Americans don't face discrimination, individually or systemically? Similar to the way that prejudice against black citizens has ties to our country's history of slavery and segregation, racism against Asian-Americans also has a long history in the US, including the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (which restricted immigration) and the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War 2. But judging by our socioeconomic standing as a whole, which has led to Asian-Americans being dubbed the "model minority," one would be inclined to shrug and say, "They're fine. They're doctors and engineers. What do they have to worry about?" That would be a gross reduction of the Asian-American experience.

The Inherent Prejudice Against Asian-Americans

Like many teens, regardless of race, my high school years were challenging at times. Bullies have many reasons and motivations for tormenting others. One widely recognized psychological explanation is that they're insecure themselves and therefore they lash out at others to compensate for inner demons. But not all of my bullies fit into this neat explanation. Many of them were average kids — well-rounded, popular, even. These were the types of kids who would volunteer for Habitat For Humanity and help an old lady across the street. Aside from their encounters with me, many of these kids weren't bullies at all; they tormented me because of an inherent prejudice they thought was normal.

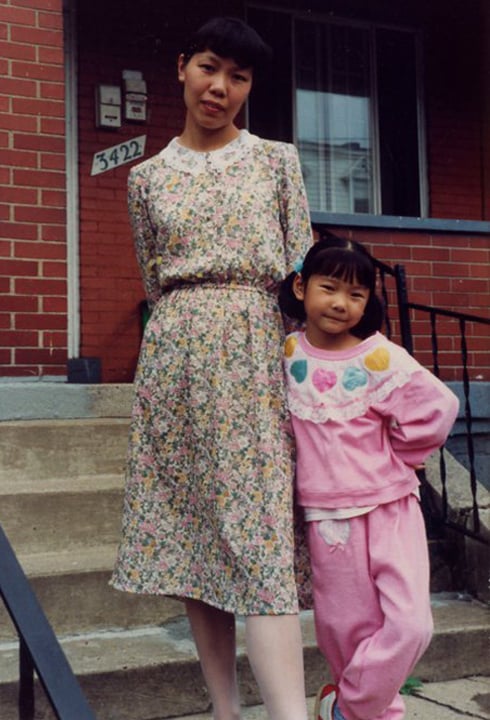

The author as a child, with her mom.

"I don't want my kids to look Chinese!" A boy yelled loudly in biology lab when we were conducting an experiment on genes and traits. His lab partner giggled. They knew I could hear them. I was working in the row in front of them.

"Chinese people can't cry; their eyes aren't big enough," another boy stated matter-of-factly in social studies class while we were watching a film on Chinese culture. I don't remember why the people on screen were crying, but knowing those educational films, it was probably a segment on something harrowing, something that would normally evoke sympathy.

Sometimes the prejudice became physical. I was sitting in the auditorium of our high school theater during rehearsal for My Fair Lady when I heard a voice in the row behind me whisper, "Not only does she have white hair, but she's also Chinese." Another voice giggled. Then, in an act that left me in pure disbelief, one of them tugged and pulled out one of my white hairs. (I've had white hairs since I was 14, which is not abnormal for Asians.) They laughed. I sat there, trying to pretend like what was happening was not happening. Then, they did it again. This time, I turned around and asked, "Did you just pull my hair out?" They just laughed. My friend, who had been sitting next to me the whole time, said and did nothing.

That wasn't the worst physical encounter. Pulling someone's hair out, one strand at a time, is upsetting, sure, but does it constitute assault? Maybe not. But what happened in the lunchroom definitely does.

I was sitting with friends, eating my sandwich and minding my own business, when one boy who particularly liked to pick on me started his usual routine of making noises that sounded like mock Chinese within earshot. Then, out of nowhere, he threw an aluminum lid at my head — or tried to. It whizzed past me and hit the floor, but had it struck me, I would have probably sustained a gash. What did I do? Nothing. I was terrified. My friends called him an assh*le but didn't dare face him either — how could you blame them? I didn't realize at the time, but our collective inaction, mine especially, was a microcosm of the imbalance in society's fight against racism.

I remember feeling hopeful when witnessing my fellow classmates react with outrage at the horrors of American slavery, Jim Crow laws, and the violence that they bred. Surely, these same kids would stand up against someone hurling a racial slur at me from across the room, right? Nope.

It was this same wishful thinking that I carried with me on the Eracism trip. This was a trip specifically aimed at raising awareness of racism. It should have, by all means, opened my eyes to the strength of unity among young people. It should have inspired me, instilled new hope in me that for every racist kid, there were dozens more who wanted to put that kid in his place. I couldn't have been more wrong.

As shockingly appalling as my experience on the Eracism trip was, my Indian peer's complacency and desire to stay out of the conflict was the most alarming part. Years later, I realize that this complacency is what keeps the Asian-American struggle out of the public discourse, that perpetuates the harmful "model minority" stereotype, which has been used by white Americans to pit one minority group against another. The mentality essentially boils down to this: "If Asians can succeed in America without causing trouble, why can't you?" But exhibiting outward complacency does not necessarily equate inner peace. Even if one does not react to prejudice, simply enduring it can cause acute psychological effects.

Hair pulling and lid throwing aside, there were countless instances in between, which were perhaps imperceptible to anyone who was not Asian. For example, a boy nonchalantly saying, "This old chink lady . . ." while walking right behind me down the hall or the persistent chorus of mock Chinese that followed me from classroom to classroom, to the mall and grocery store, and even on sidewalks. I was constantly anxious that someone near me was going to make fun of me and my race. As a result, I've developed a superpower: my ears can pick out the words "Chinese" in even the densest crowds.

Besides being a human sensor for nearby prejudice, experiencing racism on a regular basis during my formative years manifested in another way. I had never recognized this condition before my friend, who is half Korean, half Caucasian, put it into very simple and straightforward terms: "Every single person I meet, I have to wonder beforehand, 'But what if they're racist?'" Huh. Yeah. I guess that's a thing I do too, I thought. At least that was the case all through college, before I moved to New York City and its diverse population slowly dismantled the suspicious scope through which I met every single human. I had yet to even hear the term "white privilege" at the time, but I already fully understood what it meant.

Clint Smith writes about this subconscious — or sometimes conscious — anxiety in the black community in his piece "Racism, Stress, and Black Death" for The New Yorker. Of course, the context he describes is far more grave than my adolescence. As a result of this country's long history of racial profiling, which has led to dozens upon dozens of fatal police shootings, black men and women have developed "profound psychological implications" that endure and linger after an incident of profiling is over, Smith writes: "Simply perceiving or anticipating discrimination contributes to chronic stress that can cause an increase in blood-pressure problems, coronary-artery disease, cognitive impairment, and infant mortality."

Although I have experienced the same anticipation of discrimination, my anxiety pales in comparison to the perpetual fear that one's life may be in jeopardy that the black community feels all too often. The psychological ramifications I was left with were far less harmful, ranging from a blanket distrust when meeting new people to a naive acceptance of Asian fetishism, because compared to the anti-Asian sentiment I had experienced, any kind of appreciation was a welcome change.

The Start of a Movement

Make no mistake: I have been fortunate in my encounters with racism. I have yet to experience real violence or institutional discrimination, but that does not mean that either does not exist. While there may be far fewer hashtags advocating for Asian-American rights, there is indeed a cause for them.

On Oct. 9, New York Times editor Michael Luo published an open letter to an anonymous woman who had yelled at him to "Go back to China!" In recounting his personal story, he opened up a dialogue with a national audience, and soon his story started trending. In the days that followed, the Times published several follow-up pieces, including a video of Asian-Americans recounting their own instances with racism using the hashtag #thisis2016. This is exactly the kind of dialogue that needs to be started in order for Asian-Americans to join the overall conversation on race.

In June of this year, 17-year-old Michael Tarui launched a hashtag, #BeingAsian, that has been used hundreds of times to describe what it's like, well, being Asian, whether that's being met by strangers with "ni hao" because they automatically assume you're Chinese or being perceived as "not Asian" enough if you're multiracial.

In May, a group of Asian-American cultural leaders, including comedian Margaret Cho, YA author Ellen Oh, and The Nerds of Color founder Keith Chow, launched the hashtag #whitewashedOUT to raise awareness of Hollywood's tendency to whitewash Asian characters. One tweet in particular, posted by comedian Hari Kondabolu, cited financial motivation as a major factor: "Capitalism fuels Racism. Whites are cast over Minorities, not out of hatred, but because of the assumption of higher profit.#whitewashedOUT."

This assessment extends beyond Hollywood. A former colleague of mine experienced this profit-driven discrimination at a media company. The site's "Identity" category on the homepage listed black, Hispanic, and even "white privilege" as topics. But according to her, when she asked her manager why there was no Asian or Asian-American subcategory, he responded, "Asian doesn't sell."

This is mild on the spectrum of anti-Asian discrimination. While the vast majority of hate crimes are directed against African-Americans, Asian-Americans are far from exempt. According to an NBC News report from February, members of New York's congressional delegation urged the NYPD to investigate a recent spike in crimes against Asian-Americans in the city. In a letter, they pointed out that between 2008 and 2014, "Asian/Pacific Islander" was the only group for which the percentage of victims rose for every type of crime. One month later, leaders in NYC's Asian-American community met with police officials to address their concerns that these crimes were not being labeled hate crimes, even though they believed the victims were targeted because of their ethnicity.

As heinous as these crimes are, they don't fit neatly into the law enforcement and frayed community narrative and therefore struggle to fit into the collective conversation on race. However, as this 2014 Time piece points out, there have been plenty of cases of police violence against Asian-Americans in recent history. Perhaps the fact these incidents make up a small fraction of police brutality cases overall explains why no movement to advocate for Asian-American rights has ever solidified to gain national attention.

So where does that leave Asian-Americans in the fight for racial justice and equality? I don't pretend to have the answers, but if my experience is any indication, then I think it all comes down to not staying silent. We must join the conversation, like Luo did.

Asian-Americans must remember that, despite the different circumstances, they need to stand united with other minority movements like Black Lives Matter, because justice for one group is a precedent for justice for all. And those who would unabashedly support Black Lives Matter should not hesitate to stand up to discrimination against their Asian-American peers — this is something I hopelessly wished for in high school. Take inspiration from the many Asian-Americans who actively support the Black Lives Matter movement and use your voice; use your vote. For other minority groups and for your own. This is precisely the type of social awareness that needs to be created and championed in order to give Asian-Americans a seat at the racial justice table. It starts with us, because we owe it to ourselves to enact change.

If I've learned anything at all from 28 years of living as a minority in America, it's that the ongoing fight to end racism should not be a segregated effort. Though there are different nuances that plague the Muslim community vs. the black community and there are prejudices in the Latino community that Asian-Americans will never understand, we all have one common thing uniting us: we all want to be treated equally. And, at the very least, that includes not being discriminated against on student field trips to end discrimination.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this story contained a lead photo featuring actress Constance Wu, which mistakenly implied that she participated in the story. Wu was not involved in the writing of this story, nor was she a source. POPSUGAR apologizes for the error.